How the South Asian Bridal Industry Built a WhatsApp Empire | India

Oonce a year, between December and February, brides-to-be and their families from across the United States and Europe flock to India and Pakistan to escape the cold and winter, visit family and, perhaps most importantly, shopping for wedding attire.

Designers and retailers are preparing for the influx of non-residential Indians, or NRIs, by setting up sales, pop-up events or previews of their upcoming lehenga cholis, anarkali and saree lines.

But the pandemic has slowed the NRI season, with spikes in infections and travel limitations making it difficult for parents of the bride and groom to make the long trip to cities like Hyderabad, Mumbai, Delhi or Gujarat.

In response, many retailers have moved an increasing portion of their business online, increasingly turning to two platforms to facilitate the close collaboration between creator and customer that is often required to complete a purchase. only dress: Instagram and WhatsApp.

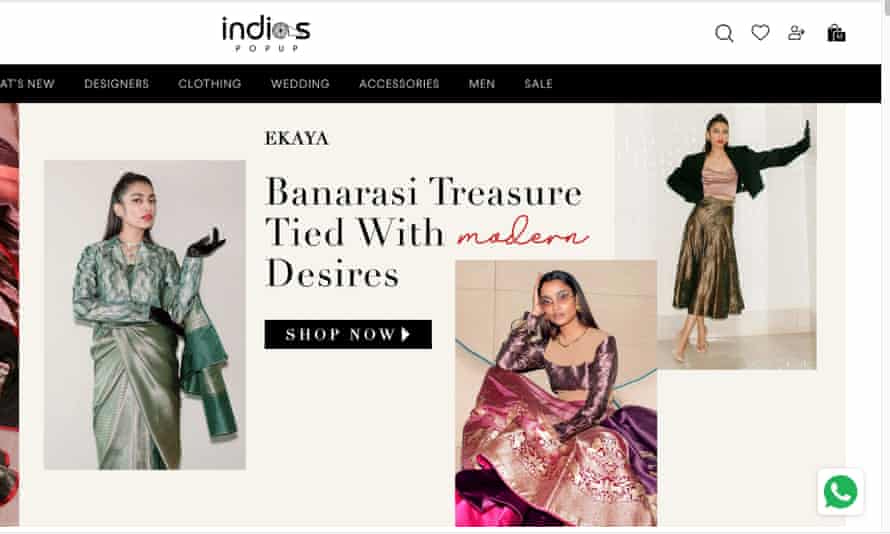

VSbrowse the websites of many major Indian clothing stores these days and you will find a WhatsApp icon at the corner of the page. Want to customize a specific product? Click on the link to start a WhatsApp conversation with the store.

With 2 billion users worldwide, WhatsApp has for years been ubiquitous in many parts of the world, although Americans have been slower to adopt the messaging platform as their primary means of communication. Even among second-generation South Asian Americans, WhatsApp is often seen as the platform on which their mothers and aunts receive and spread misinformation and chain letters.

The pandemic has accelerated the adoption of WhatsApp as a place not only to communicate, but also to coordinate expensive and personally important purchases among South Asian diasporas. While Instagram largely serves as a discovery platform for retailers, WhatsApp is where customers and store owners communicate.

Shubika Davda’s brand Papa Don’t Preach, known for its bright colors and modern take on lehenga choli and other traditional clothing, was one of the first to start as an e-commerce brand in 2011, according to Davda.

Davda is introverted and she was looking for a way to launch a brand without having to interact too much with customers in person. “It would wear me down,” she said. “Because with Indians, especially when buying a custom-made outfit, a meeting can take up to three and a half hours with the whole family.”

She launched Papa Don’t Preach on Instagram, using her account as a vehicle to tell her company’s story without input from fashion critics and without needing to wait for fashion weeks to feature her lines. “I finally felt like I was taking the power back into my hands,” she said.

But she quickly realized that customers needed a way to instantly communicate with the store. “No matter how much information you put on the website and how accessible your phone lines are, people want to converse with you, especially if they’re buying an expensive outfit, especially if it’s custom-made,” said she declared. So, in 2018, the company integrated WhatsApp into its platform. Since then, the brand receives 50 new requests per day. Each request can take several days before the customer buys the dress.

Davda, like many other retailers, uses a business WhatsApp account, sharing catalogs on a contact page and products through the app’s “stories” feature. The brand also uses WhatsApp to guide customers through the garments via video chat and discuss fit. Customers often respond to photos sent by the brand with a screenshot that the company can annotate directly on the platform. Davda has a dedicated person to respond to WhatsApp messages and plans to add another to work late to respond quickly to international customers.

OWhen shopping for dresses, South Carolina-based Kena Patel has never had many brick-and-mortar options. Like many in the South Asian diaspora, she relied on her father to bring back suitcases full of dresses from his trips to India every year.

When it came time to shop for outfits for her cousin’s wedding during the pandemic, Patel felt she had no choice but to shop remotely. She didn’t want to take any risks – her father put her in touch with a contact at a factory in India whose dress quality he knew and trusted. Still, shopping for intricately designed, custom-made lehengas online that could cost hundreds to thousands of dollars was a new experience. And at the start of the pandemic, not all stores were equipped to support international online sales.

Allow Instagram content?

This article includes content provided by instagram. We ask for your permission before uploading anything, as they may use cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click on ‘Allow and continue’.

To show Patel his options 8,500 miles away, a store owner in India went through his shelves item by item, Patel said, showing him several options at once over a WhatsApp video call. Patel specified the “exact embroidery” she wanted and the shades she was looking for. It was almost as if she was browsing the store herself, she recalls.

While coordinating sales on WhatsApp isn’t an entirely new process for India-based retailers, it took the pandemic for many to realize the issues. Shreen Khan, a Los Angeles-based journalist, said she designed her wedding dress at a store in Hyderabad on WhatsApp in 2019. Similar to Patel’s, her family also knew the shopkeeper. Still, she wouldn’t recommend the process to anyone, though she admits it may have improved over the years.

“There was a time difference. There were language barriers, there were connectivity issues, and then it was also Ramadan,” Khan recalls. “So your physical and mental capacity is different when you’re fasting and when traders are too.”

Khan also showed the shopkeeper different styles, embroideries and colors she wanted and the shopkeeper would send him photos or video call him to show him fabrics and other options. But communicating via WhatsApp seemed like a new concept for the store, which made it even harder to figure out what exactly she was buying. Did the time of day influence the color of the fabrics in the photo? And how could she gauge the touch of a fabric compared to the video?

Khan ended up happy with how the dress turned out, but she said the color of the top was different than she expected. “It was still beautiful but I think that was one of the things that was lost with being in person and being able to physically select that exact fabric.”

Jo Today many retailers are still figuring this out and some are more reliable than others. And unlike in the US, there’s no comprehensive review culture where shoppers can see what others’ experiences have been with products, designers or retailers. Patel, who has been shopping via WhatsApp since the pandemic began, said she had seen it all.

“I feel like none of my experiences were just average,” Patel said. “They were either really good or really bad.”

Two and a half years later, Patel has turned his online shopping experience into a science. She doesn’t buy anything without a little detective. She Googles every brand and even uses Google Lens, the company’s image recognition software, to determine whether images of clothes on certain websites or their designs were pulled from elsewhere. She tests brands by buying cheaper items before investing in something more expensive. “It’s a lot of experimentation,” she says.

“For boutiques in the United States, you’ll probably find something about them on any social network,” Patel said. “Whereas with these shops in India, sometimes you find nothing. So I’d much rather spend my money somewhere I’ve worked with before.

Even for American brands catering to South Asians, WhatsApp has sometimes become the preferred means of communication. Archana Yenna, founder of Indiaspopup.com, a Dallas-based retailer that distributes high-end Indian designers in the United States and Europe, said the company decided to use WhatsApp after experimenting with several other management platforms. of the customer relationship. “Believe me, innovation really sucks at this point,” Yenna said.

She said Instagram’s shopping option is not well suited for Indian e-commerce because if the retailer doesn’t ship the product within seven days, the customer gets a refund. Many of his orders can take eight weeks.

While transactions still happen on company websites, WhatsApp, unlike those other platforms, had several advantages, Yenna said. Chat history made it easy to pick up conversations with customers where they left off. It was also much easier to share a lot of files and resources on WhatsApp than on Instagram or email. Group video calls allow parents of the bride and groom, who in South Asian families often do the lion’s share of shopping, to call their daughter or son whenever they want their input.

In fact, Yenna said she found the fastest users of WhatsApp as a way to design and discuss buying clothes were millennial parents who were already used to communicating with their own families and friends across South Asia via WhatsApp. “Our market is expensive, so you’re dealing with mothers and aunts,” Yenna said. “These aunts and the clientele we deal with, they are very used to WhatsApp and they love it. They are not used to email. When we ask them to email us details, it is foreign to them . »

There are also obstacles. WhatsApp is still limited in how it works with major brands. Yenna said it was not easy for customers to browse through her company’s huge clothing catalogs. It is not possible for several staff members to serve the same number. WhatsApp also still does not allow transactions on the platform, although a company spokesperson, Adam Landres-Schnur, said that was in the works.

“WhatsApp is definitely a powerful platform for customer service,” Yenna said. “Not for e-commerce.”

Comments are closed.